What you see is what you get - #432

In Hidden Valley Road Robert Kolker summarizes one line of thinking about a source of schizophrenia as the inability to tune out very much of the constant stream of incoming stimuli. The theory goes that most of us can usefully ignore a lot of the noise of life—we hear less of the wind to focus on what people are saying or we give more credence to our actual plans than our fantastical daydreams—while some of us are unable to triage amongst these incoming stimuli, giving equal attention to everything and thus losing the thread of what actually matters. I have no idea if this is a good summary of the research or if the research has moved on in the years since, but the concept of subliminal abilities to screen out or focus on some of what we encounter in the world is intriguing. Is our internal filtering trainable? Is it adversely trainable?What could the things we automatically ignore be telling us? How might we adjust what we are able notice?Over the years, I've linked to more than a few thoughtful essays about topics sundry and various. The smart kids at The Atlantic's consulting outfit used to call this low/high: low topics given thoughtful-to-academic treatments. You might recall the deep dive into puppetry I posted a few months ago under the heading "better than it has any right to be." The top link below is another along those lines: what can one urban gardening essayist make of their compost heap? A whole lot, if you give them a chance. It's fun to think of us all as little Wendell Berrys, poking about in the dirt with a stick, returning with not just a turnip but also with earth-shaking poetry and prose. I'm sure I succumb to the the temptation, what with my little trees in pots. What we notice and how we give it attention and what we expect from the interaction is who we are.

That's what Craig Mod, savior of some Japanese countryside entertainingly argues in the second essay linked below. His experience of guiding his attention, of training himself to filter endless stimuli in new ways, presents something positive. We can, by peering a bit more intently, or a bit askew from our normal pose, get more from this world. Mod's "close look" seems to me a kind of conversion.

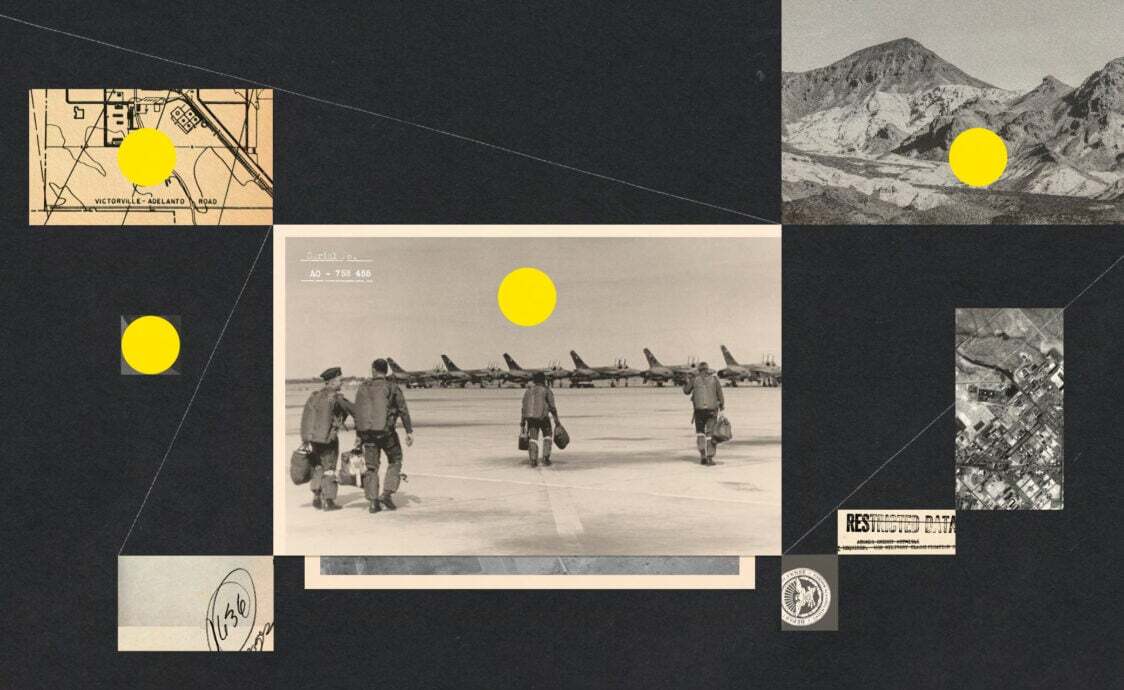

As warming as compost and close-looking are, the Harper's piece is the most haunting of my reading this week. We begin with a US Airman's poorly remember encounter with some sort of chemical waste at George AFB in California. He got very sick, eventually was discharged from the service, and has spent the rest of his life looking closely at that event. Our reporter, open-minded in the best sense, first wonders if they've stumbled onto one of those vast, inhumane coverups only the world's largest bureaucracies are capable of. After delving in, they come to a more sobering realization: a man whose paid attention only to chemical waste and human harms from it for decades may no longer be a reliable narrator, even of his own experience. What if paying attention to endless suits and hearings and forms and FOIAs takes even the most valiant down the conspiracist's path? The piece doesn't come to a clear conclusion, leaving us to draw our own. Each of our conclusions will depend entirely on which aspects of the story we allow past our filters and, willfully or not, which we pay attention to.

What you see is what you get.

Reading

On Compost

On Compost

Composting as a hopeful practice that connects us to nature and promotes ecological recovery.

Looking Closely is Everything

Looking Closely is Everything

How the pandemic taught me to look closely at the world, and how I hope to carry that forward out the other side

Radioactive Man

Radioactive Man

On (maybe) unraveling a government cover-up